ETFs, unlike mutual funds, do not charge a load fee. They are traded on an exchange and may incur brokerage commissions, which vary by firm but rarely exceed $20.

What is Commission?

A commission is a fee that our broker would charge us for executing the trade and for doing the paperwork behind, getting us the shares that we bought, or the ETF that we bought. A lot of that is automated these days and many brokers are no longer charging commissions. As time goes on, the less and less they're going to be charging commissions. So if our broker is charging us a commission, it could be time to talk to them about either long that commission, dropping it completely, or more likely finding a new broker that doesn't charge a commission. The Commission fee is mostly avoidable these days.

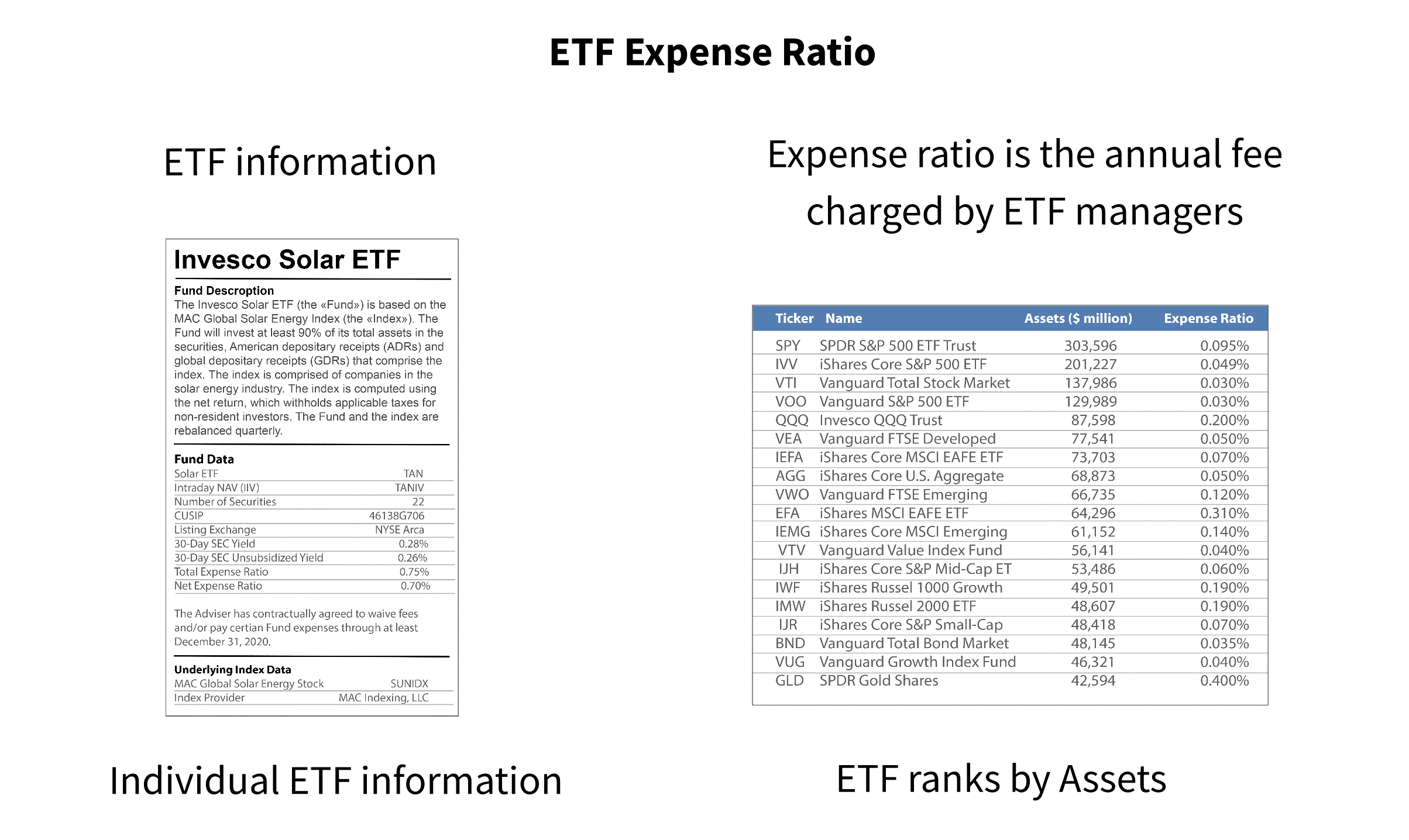

What is Expense Ratio?

The annual fee charged by the exchange-traded fund manager to cover operating expenses is referred to as the Expense Ratio.

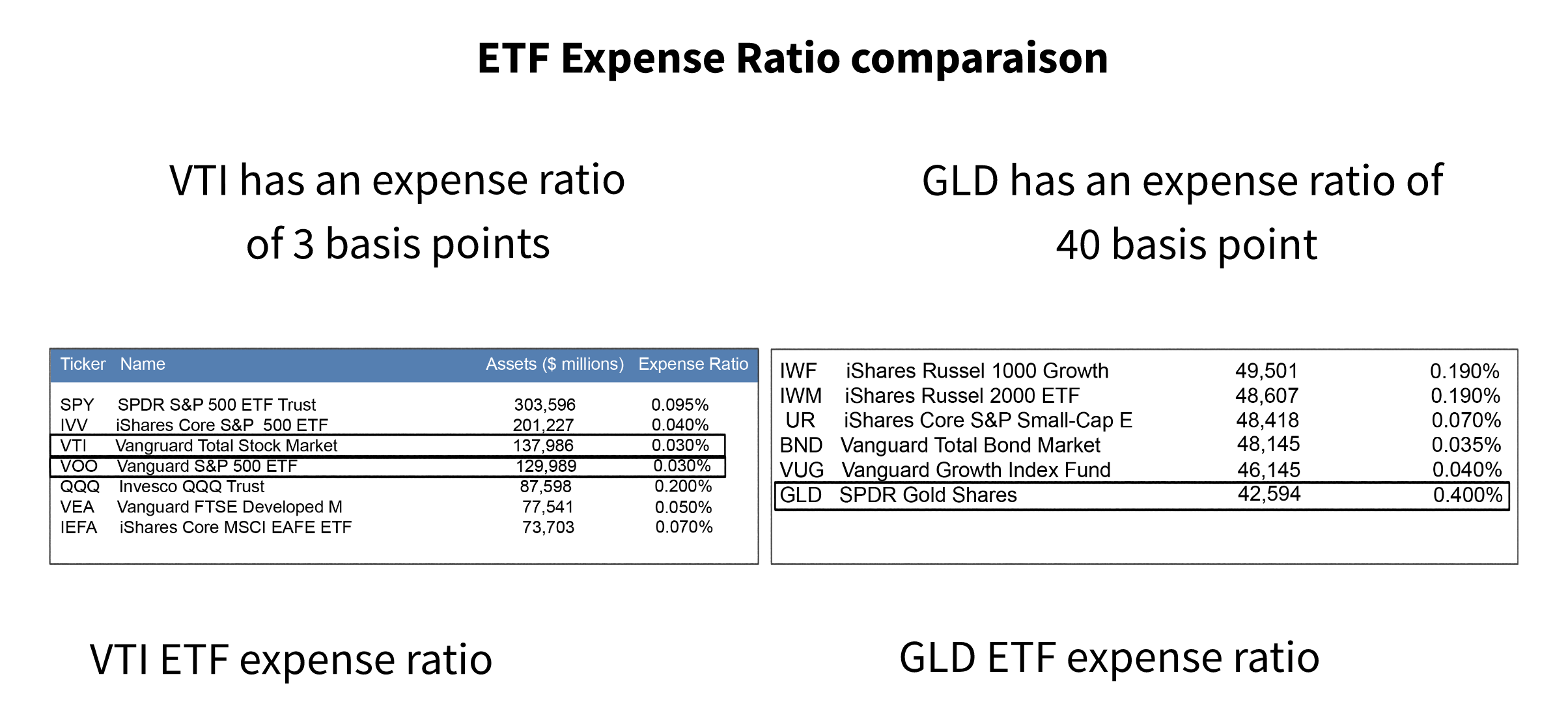

This is a short list of some of the largest ETFs out there:

We can roughly see how many assets they have in each of the funds, and the part we care about is how much their expense ratio is. This is the most popular ETF fee out there, and when oftentimes, you might hear people say “Their fee is blank” and this is what usually what they're talking about. We can see that these fees run from as low as 3 basis points to as high as GLD down here, which is 40 basis points.

Outside of this, there are some ETFs out there that don't have any fees and there are others that are much higher than these. However, we'll just stick with these examples for now. Obviously, we want this fee to be as low as possible.

Let's look quickly at how ETF fees actually work to help us get a better understanding of what some others call implicit fees.

So we're the investor, and we're gonna go out and buy an ETF. Now, this is where we would be charged as commission. If we're at a brokerage firm that has one but let's imagine we're not being charged one, we'll get rid of that.

Now, this ETF is going to be investing in something, maybe it's a bunch of stocks, or bonds, or commodities, or whatever it is that's what those circles represent. We're investing, and we're likely investing in the ETF because one of the advantages of buying ETFs is we tend to buy a whole portfolio all at once.

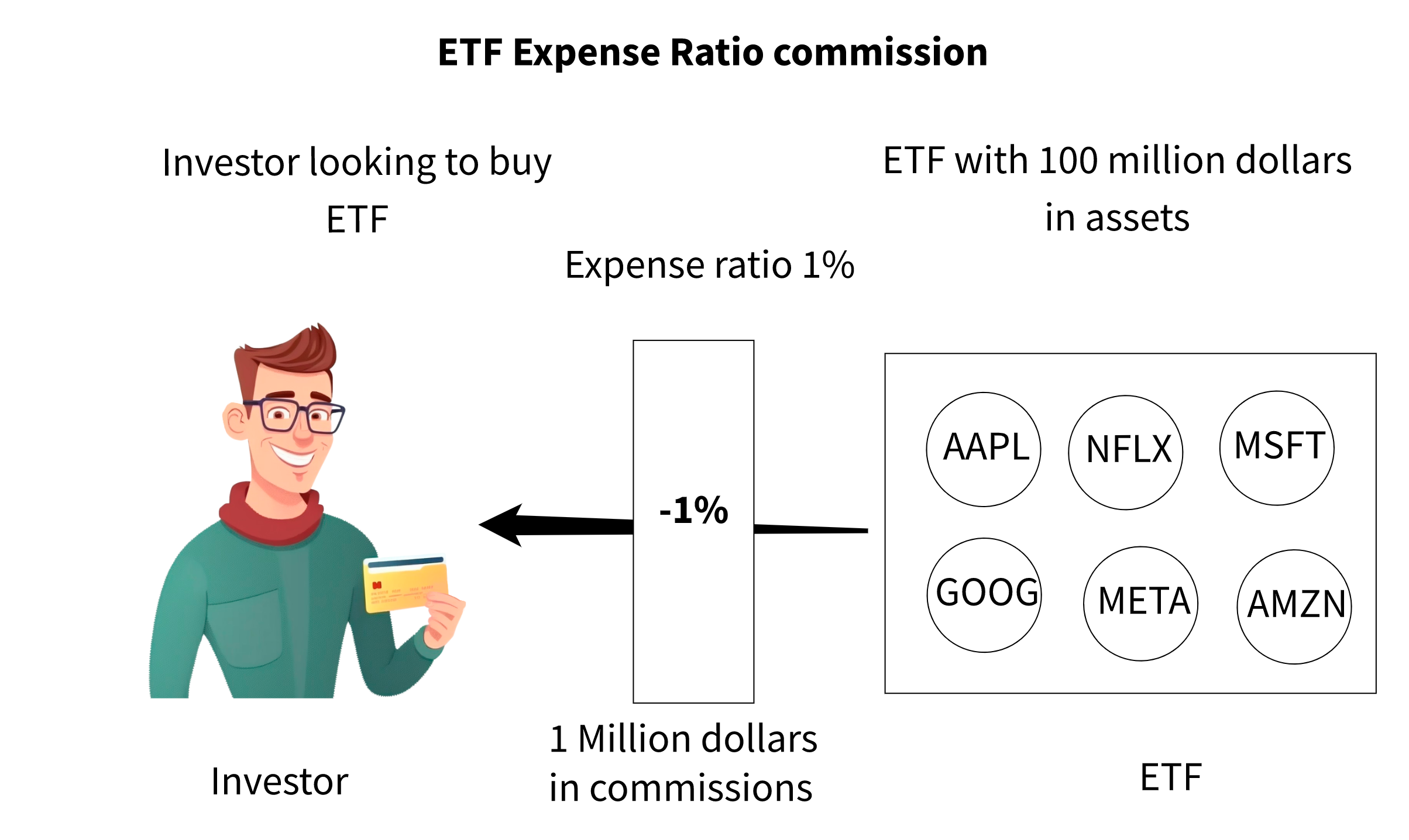

Let's imagine that this particular ETF has $100 million, this ETF is managed by a fund manager, maybe the ads Vanguard, iShares, or some other company, but either way, it's going to be managed by a fund manager. So when the time comes for that fund manager to get paid, their fee comes right out of the pool of assets that the fund controls. If it's a hundred basis points which is the same as 1%, this fund has 100 million dollars in it, they will get a million dollars.

To calculate how much an investment firm made from its expense ratio, you would multiply the asset under management (AUM) by the expense ratio. In the case of ARK Innovation ETF, the AUM is 14 billion dollars and the expense ratio is 0.75%.

14,000,000,000 * 0.0075 = 105,000,000

So, the firm made 105 million dollars from its expense ratio.

We as investors never see that happen since it all happens within it all happens behind the scenes of the ETF. Obviously, we want this ETF fee to be as low as possible and they call this fee the expense ratio. We want to keep that in the back of our mind, that in expense ratio, we ideally have no commissions or a low expense ratio.

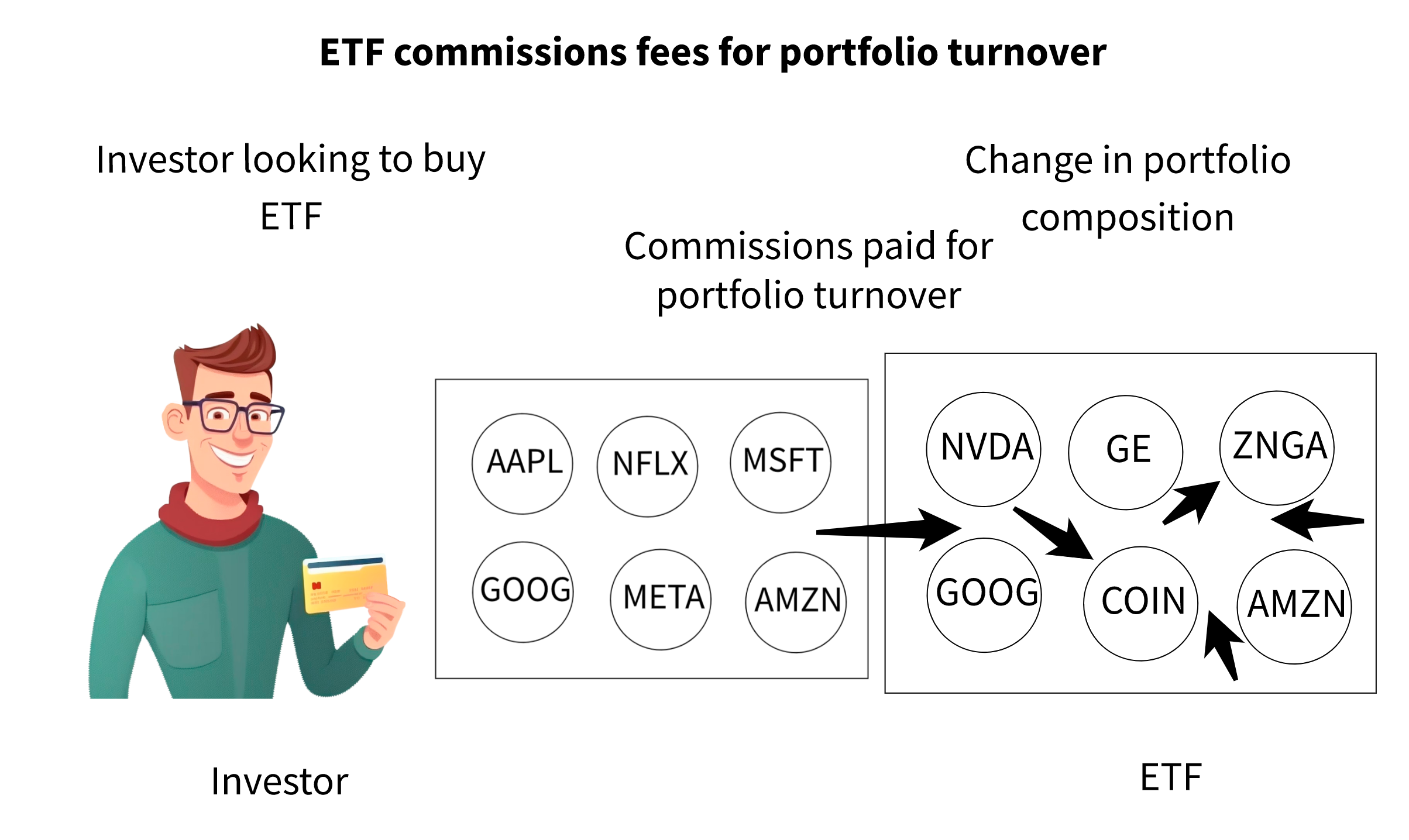

Let's take another example, so this fund manager is managing this portfolio of stocks, and let's say, as time goes by they no longer want one of the stocks or don't meet the rules of the fund, so they sell that stock. What do they do generally, they replace that stock with perhaps a different stock or bond. The odds are, even if we're not paying a commission, the odds are that the ETF fund manager is paying commissions to their firm.

Every time they buy and sell a stock or a bond, then it is in the ETF. There are likely to be commissions charged in those transactions and that is not accounted for in the expense ratio. For that, we want to look at something known as “Portfolio Turnover”. We want our portfolio turnover to be as low as possible, because the more the fund moves in and out of different positions, the higher the turnover ratio will be.

Ultimately, that will lead to more transaction costs like commissions, and it could lead to higher taxes if the fund has to pay capital gains tax, there could be other fees tied to them moving in and out of positions, so they're going to define all of this in the company's perspective. Broadly speaking, we want a lower turnover ratio because that is likely to lead to fewer overall fees or overall implied fees that are not included in the expense ratio.

This brings us to another sort of implied fee, and it's not really a fee but it's something that could end up costing us more, and it is known as the bid-ask spread. When we go on, we buy stock or an ETF.

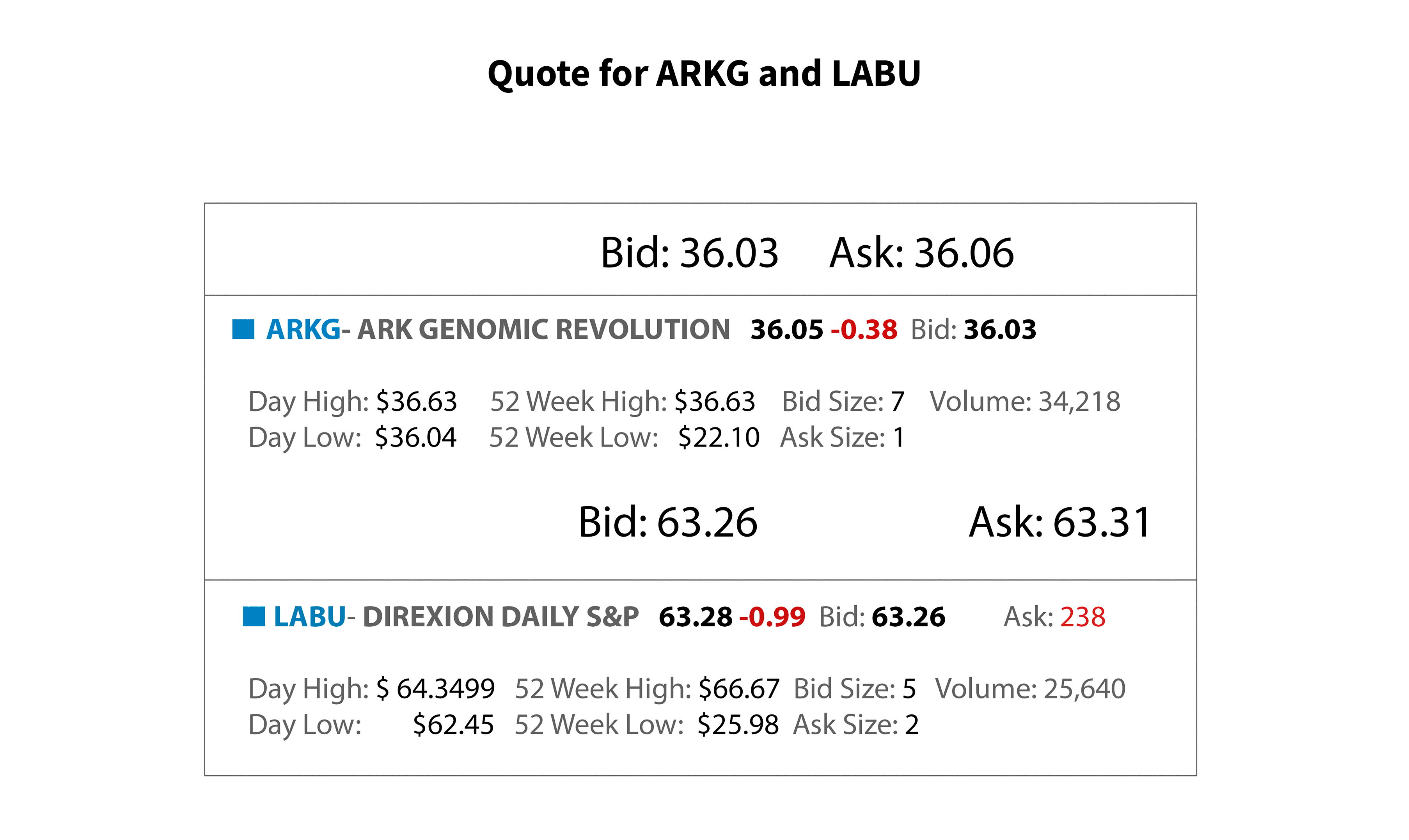

If this would hold true for both of them, then you might get a quote like this.

This is a quote for SPY, and as we could see, the bid for SPY is 322.05 and the ask is 322.06, just a penny apart. That's pretty good, but the higher this spread is the more the broker makes. What we have to remember is if we were to place a market order and we want to buy a stock or an ETF at the market price, we buy it at the ASK price. If we wanted to sell or sell at the bid price. You're always going to get the worst price available and we want this spread to be as low as possible. Generally, with the higher liquid and more popular ETFs, this spread is going to be very small. However, if we look at something like ARKG, we can see their spread is 3 cents, then if we switch to LABU there they have a spread of 5 cents.

This may not sound like a lot, but we are talking 5 cents per share. So depending on how many shares were bought, this could make a meaningful difference.

Why pay a nickel more if we don't have to?

One way to get around this is, instead of buying or you placing an order at a market order, you could do it at a limit order and try to close that gap a bit.

From the ETF standpoint, if we're investors and in the long run, perhaps the Nikolas share doesn't matter all that much. However, it's worth remembering or at least being aware of and then we could decide as we get into that position. Does it ever make sense to pay a higher fee for an ETF? The answer is, absolutely!

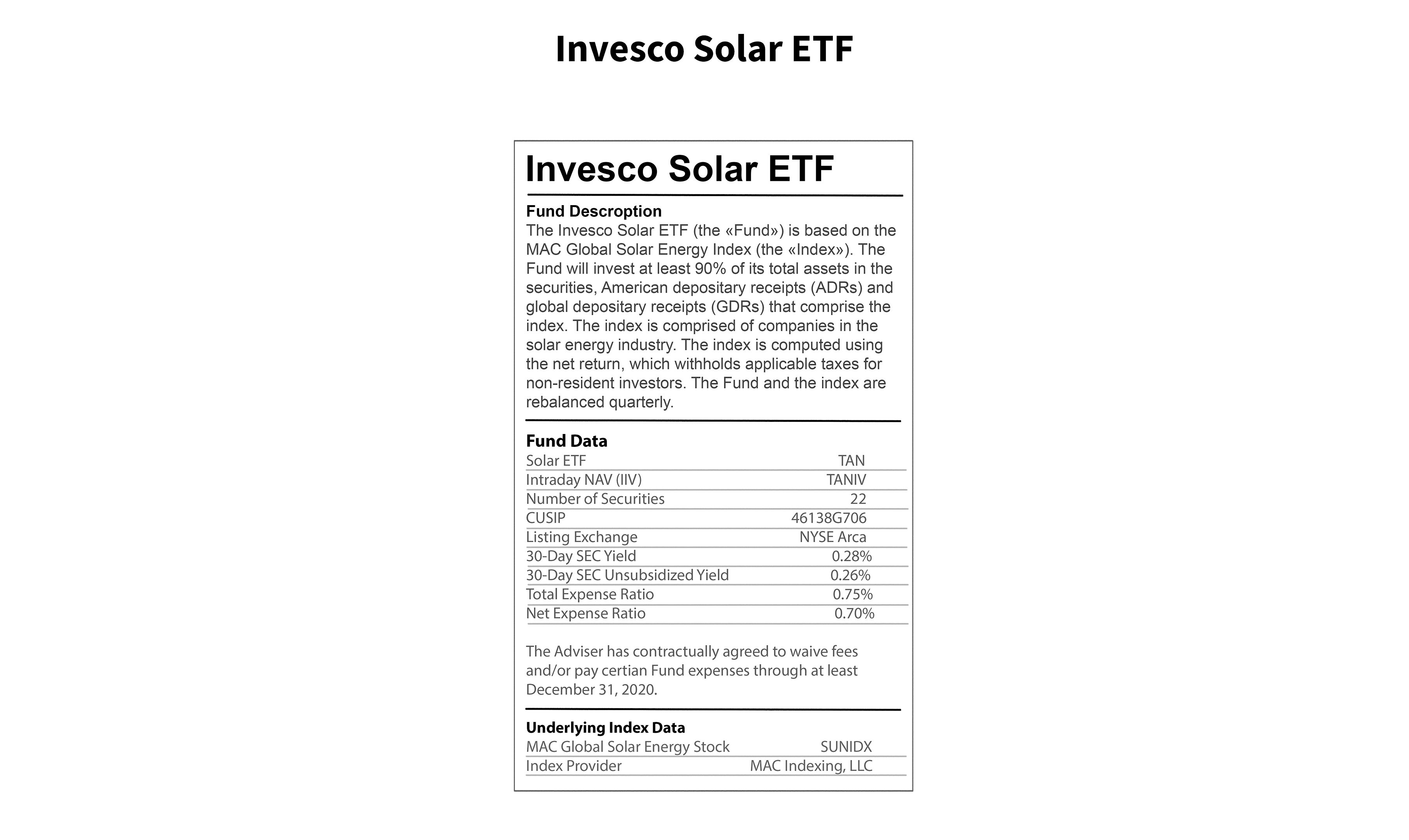

Let's start with this ETF:

This is an ETF called Invesco Solar ETF, ticker symbol TAN. Obviously, they focus on the solar industry but their fee is about 70 or 71 basis points and it is 7/10 of 1%. By today's standards, many people would look at this fee and say it's very high. However, this is a very specialized ETF, and if we're interested in an ETF like this and interested in investing in the solar industry, then it could serve a very specific purpose in our portfolio. If that's the case, we might be willing to pay a higher fee.

This ETF as an example in 2019, has a total return of more than 65% and that's more than double what the S&P500 did. We could have paid 3 basis points for S&P500 ETF, or we maybe pay 70 basis points for this ETF. Hindsight being 20/20, this one would have made more sense. We bring this out to illustrate that if we let our research lead us to a great potential opportunity for a sector, a group of stocks, or bonds, then we wouldn't avoid investing in a particular ETF just because the expense ratio looks high relative to broad or very popular ETFs like SPY, or any one of the Vanguard ETFs. Perhaps, our research is correct and we're willing to pay a higher fee, and ultimately that gives us broad access to a group of stocks or bonds that could ultimately lead to our portfolio outperforming.

Key Takeaways:

1. ETFs do not charge a load fee, but may incur brokerage commissions which vary by firm.

2. The expense ratio is the annual fee charged by the exchange-traded fund manager to cover operating expenses.

3. We want the expense ratio to be as low as possible and to look at the portfolio turnover to avoid implicit fees.

4. We also want to look at the bid-ask spread to avoid paying more than necessary.

5. In some cases, paying a higher fee for a specialized ETF may be worth it if it leads to portfolio outperformance.